The Catholic Church upholds four Marian dogmas:

- Mary as Mother of God

- Perpetual Virginity

- Immaculate Conception

- Assumption into Heaven

These teachings are not presented as devotional preferences or theological opinions; they are declared binding truths, revealed by God and proclaimed by the Magisterium as necessary for belief.

This reflection does not dispute that Mary holds a special place in salvation history. She is, after all, the woman who said yes to the Incarnation. But it does question the necessity, coherence, and implications of certain dogmatic claims made about her life and nature.

Reflections on the Four Marian Dogmas

1) Mary, Mother of God (Theotokos)

Summary

- Dogmatically defended at the Council of Ephesus, 431 AD.

- Declares Mary as the Mother of God, not just of Christ’s human nature.

- Rooted in Luke 1:43: “Mother of my Lord” – upheld to defend Christ’s full divinity.

- Meant to protect orthodox Christology (Jesus = one divine person with two natures).

- Biblically grounded and accepted across Catholic, Orthodox, and some Protestant traditions.

Declared at the Council of Ephesus in 431 AD, this dogma affirms that Mary is the Mother of God because she gave birth to Jesus Christ, who is fully God and fully human. The title Theotokos (“God-bearer”) was a defence of Christ’s hypostatic nature.

It upholds orthodox Christology by affirming that the one born of Mary is God Himself. But it also elevates Mary’s place in salvation history, not by turning her into a goddess, but by recognising her singular role in the Incarnation.

This teaching is not controversial. It reflects orthodox Christology and rests on strong biblical ground. When Elizabeth greets Mary as “the mother of my Lord” (Luke 1:43), she is acknowledging the Incarnation: that the one in Mary’s womb is no ordinary child.

2) Perpetual Virginity

Summary

- Dogmatically defined at the Lateran Synod, 649 AD.

- Asserts that Mary remained a virgin before, during, and after Jesus’s birth.

- Heavily relies on early apocryphal sources (e.g. Protoevangelium of James).

- Catholic teaching uses “brothers of Jesus” to refer to cousins or kin, not siblings.

- Critiqued for implying that marital intimacy undermines sanctity or virtue.

The Church teaches that Mary was a virgin before, during, and after the birth of Christ. The main text cited in support, outside of the canonical Gospels, is the Protoevangelium of James, a second-century apocryphal text that presents Mary’s virginity as sacred and untouchable.

If this doctrine is so central, one must ask:

- Why is its primary source not included in the canon?

- Why is the sexual abstinence of Mary and Joseph elevated to theological necessity?

The Church claims the Holy Family is a model for all families. But how can that be when the model excludes sexual intimacy, paternal biology, and a typical marital bond? Chastity within marriage does not mean abstinence. Nor is virginity, in itself, a virtue. The moral quality of one’s life isn’t determined by whether or not one has engaged in sex but by love, faithfulness, and integrity to one’s vocation.

The insistence on Mary’s perpetual virginity, then, seems less about holiness and more about a theological unease with the body, especially women’s bodies. And the implications here are not neutral. The most exalted woman in Catholicism is revered because she is a virgin. That message, intentional or not, can be spiritually alienating to women who are mothers, wives, or simply not celibate.

Matthew 1:25 plainly states that Joseph “did not know her until she had borne a son.” The traditional response to this is grammatical gymnastics. But the discomfort isn’t just exegetical, it’s existential. What does this dogma teach Catholics, especially women, about what makes them worthy of respect?

3) The Immaculate Conception

Summary

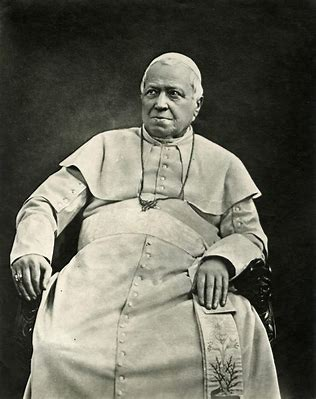

- Declared Dogma in 1854 by Pope Pius IX.

- States Mary was conceived without original sin, preserved by God’s grace.

- Not to be confused with the virgin birth; it refers to Mary’s own conception.

- Meant to affirm Mary as a fitting vessel for Christ’s sinless incarnation.

- Not found in Scripture; often criticised for lacking historical support or necessity.

- Declared infallibly, without council, in Ineffabilis Deus.

In 1854, Pope Pius IX declared that Mary, from the moment of her conception, was preserved free from original sin. The reasoning is that a sinless Christ required a sinless vessel.

But to honour Mary, must we insist she was never touched by the human condition?

To claim that Mary was without sin, personal or original, is to remove her from the very humanity she shares with us. Jesus was like us in all things but sin (Hebrews 2:17); that distinction is part of what makes him the Son of God. Mary, though highly favoured, was still human. She did not need to be pre-redeemed to carry Christ. Her holiness could have been formed through grace, not imposed by exemption.

Moreover, the idea that sinlessness is the price of veneration risks deifying Mary. And if she needed no Saviour, why does she declare in the Magnificat, “my spirit rejoices in God my Saviour” (Luke 1:47)? A sinless person does not require saving.

This dogma asks the faithful to accept not only theological abstraction but a redefinition of humanity itself. It elevates Mary by distancing her from everything that makes us real.

Read Ineffabilis Deus here.

4) The Assumption

Summary

- Teaches that Mary was taken up body and soul into heavenly glory.

- No biblical account; based on longstanding pious belief and apocryphal tradition.

- Framed as a sign of hope in bodily resurrection, especially post-WWII.

- Defined infallibly in Munificentissimus Deus, again without conciliar input.

- Raises theological concern: Why was such a major event omitted in Scripture?

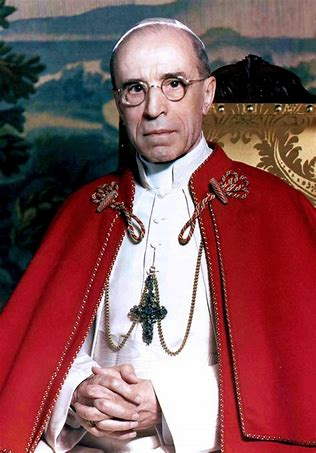

Proclaimed in 1950 by Pope Pius XII, the Assumption holds that Mary was taken body and soul into heaven at the end of her earthly life.

At the time of this dogma’s declaration, Europe was still reeling from World War II. The Holocaust, the atomic bomb, and mass disillusionment had eroded trust in human progress. In such a climate, the Assumption offered Catholics a vision of hope: that the human body, sanctified and faithful, could be taken up, not annihilated.

Unlike the resurrection appearances of Christ, the Assumption has no direct scriptural basis. The letters of Paul are silent. The Gospels say nothing. Even apocryphal sources are vague.

If this event is so essential, why is it nowhere to be found in Scripture? Why would early Christian writers, who were meticulous about the deaths of Peter and Paul (and minor characters like Stephen), omit something this momentous?

To believe that Mary is with God is not difficult. But to elevate that hope into dogma, defined as divinely revealed truth, without credible witness or apostolic testimony, raises serious questions. Especially when the proclamation comes 1,800 years after the supposed event.

Read Munificentissimus Deus here.

Why the Delay? Why the Pressure?

It’s telling that the last two Marian dogmas were defined in 1854 and 1950. In both cases, the Church was experiencing upheaval, politically, socially, and theologically. One might reasonably ask whether these proclamations were driven more by historical anxiety than divine revelation.

Timeline of Events (1848–1950)

- 1848 Revolutions Across Europe: Widespread anti-monarchist uprisings destabilised Catholic-aligned powers. Pope Pius IX lost political control over parts of the Papal States and briefly fled Rome.

→ Church reacted by reasserting spiritual authority. - Rise of Modernism and Secularism: Rationalism, liberalism, and historical criticism of Scripture were threatening traditional Church teachings.

→ Marian dogmas became spiritual counters to perceived moral and doctrinal erosion. - 1854 – Immaculate Conception Defined: Declared by Pope Pius IX unilaterally (ex cathedra) in Ineffabilis Deus, not via ecumenical council.

→ Marked the first use of papal infallibility in practice, prior to it being officially codified at Vatican I (1870). - 1858 – Lourdes Apparitions: St. Bernadette Soubirous reported that the Virgin Mary identified herself as the “Immaculate Conception.”

→ The apparitions appeared to “confirm” the dogma post hoc and helped galvanise Marian devotion among the laity. - 1950 – Assumption Defined: Declared by Pope Pius XII in Munificentissimus Deus, again without a council.

→ Came after WWII, the Holocaust, and the atomic bomb, offering a theology of bodily hope in the face of mass death.

A Brief Note on Dogma

In the early Church, dogma meant “opinion” or “judgment.” Today, it means a truth declared infallibly by the Church, binding on all the faithful. That is no small claim. And to make that claim about teachings with unclear or extra-biblical origins is deeply problematic.

- Theological Strategy: The Marian dogmas of 1854 and 1950 served as bulwarks against theological modernism and humanistic secularism.

→ By exalting Mary, the Church reaffirmed divine intervention, hierarchy, and mystery against a world increasingly sceptical of all three. - Dogma as Doctrinal Fortification: Rather than arising organically from Scripture or Apostolic tradition, both dogmas consolidated papal authority and responded to cultural crisis.

→ Raises legitimate historical-theological critique: were they revealed truths or institutional defences?

A Different Kind of Honour

The critique of these dogmas is not a rejection of Mary. On the contrary, it’s a summons to honour her more truthfully. To revere her not as a mythologised ideal, but as a woman of courage and grace, whose “yes” to God was freely given from within the same human frailty we all share.

You do not need to believe something unprovable or theologically strained to love Mary. You only need to recognise that she bore Christ into the world and loved him faithfully. That is honour enough.

We call her Blessed, the Mother of our Lord, as did all generations before us, as should all generations after us.

Leave a Reply