Introduction

Eucharistic miracles are often cited as divine endorsements of Catholic teaching: bleeding hosts, cardiac tissue woven into bread, scientific findings that seem to defy natural explanation. Many Catholics regard these events as powerful affirmations of the Real Presence. But a deeper question lurks behind the awe: if we truly believe that every Eucharist is Christ Himself, why do we need these spectacles?

In Matthew 12:39, Jesus says, “A wicked and adulterous generation seeks for a sign”. It’s a hard line, but one that calls us to examine the impulse behind this growing fascination. Are Eucharistic miracles strengthening our faith, or exposing our lack of it?

What the Bible Says About the Eucharist

The Eucharist was instituted by Christ during the Last Supper: “This is my body… this is my blood… Do this in remembrance of me” (Luke 22:19–20; 1 Corinthians 11:24–25). In John 6, Jesus makes an even more jarring claim: “My flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink.”

None of the Gospel writers, nor the epistolers, ever describe miraculous hosts turning into flesh or bleeding after consecration. The Apostles’ faith was in Jesus’s words, not in visible manifestations. The first Christians didn’t need biological evidence to believe. They took Him at His word. So why don’t we?

Transubstantiation: The Ordinary, Extraordinary Miracle

According to Catholic doctrine, the Eucharist is a miracle at every Mass. Transubstantiation teaches that the substance of bread and wine becomes the Body and Blood of Christ, while the appearances (taste, look, smell) remain unchanged (CCC 1376).

That is already radical.

So what happens when a Host bleeds or turns to flesh? The Church calls it a “Eucharistic miracle,” but that risks suggesting that the ordinary Eucharist is somehow insufficient unless confirmed by the extraordinary. This inadvertently creates a faith hierarchy: miracles at the top, the rest beneath.

It’s an unintended but profound contradiction: Is Christ’s presence real only when it bleeds?

Carlo Acutis and the Digital Codification of Miracles

Carlo Acutis, a teenager with a keen interest in computers, compiled a digital catalogue of Eucharistic miracles before his death in 2006. His website showcases documented cases where Hosts changed visibly or were preserved for decades.

While this initiative was born of devotion, it risks presenting proof as the basis for belief. The Church does not base transubstantiation on scientific findings, but on Christ’s promise. Ironically, Carlo’s well-meaning effort may draw the faithful toward a form of conditional belief: “I’ll believe if the tissue looks human enough.”

It’s a subtle but troubling shift: a pivot from sacramental mystery to spectacle-driven piety.

The Science of the Spectacle: Bias, Gaps, and Blind Spots

Many claims surrounding Eucharistic miracles are fraught with methodological issues:

- Lack of peer-reviewed studies

- Reliance on Church-sponsored labs or researchers

- Absence of independent oversight

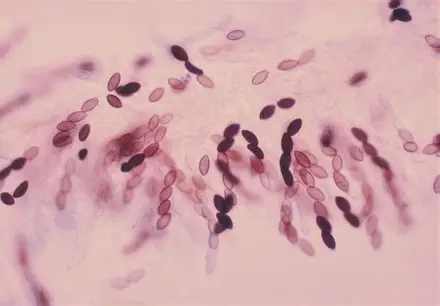

Take the 2015 case in Salt Lake City: a Host appeared to bleed. An investigation found the culprit: red bread mould (Neurospora crassa). It wasn’t a miracle, just biology.

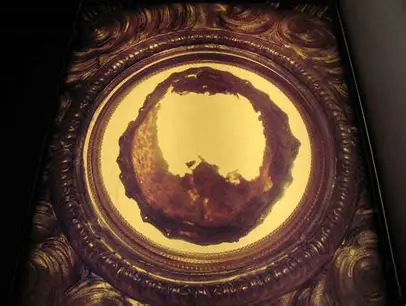

Others, like Lanciano or Buenos Aires, show histological similarities to cardiac tissue, but raise questions of contamination, chain of custody, and whether religious bias influenced the findings.

Science isn’t the enemy here. In fact, its rigour protects theology from wishful thinking.

Signs and the Hunger for the Spectacular

Eucharistic miracles appeal to a devotional imagination that craves something sensory. Seeing flesh feels more real than trusting the invisible. The modern mind, shaped by empiricism, struggles with abstraction.

But here’s the tension: transubstantiation demands sacramental faith, not sensory confirmation. To hinge our belief on physical signs is to place conditions on the very mystery we claim to uphold.

It becomes a subtle form of idolatry, not of false gods, but of false assurances.

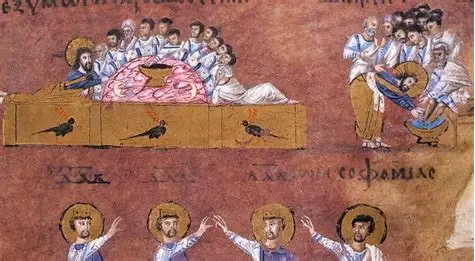

What the Early Church Believed (and Didn’t)

The Apostolic and Patristic tradition believed in the Real Presence without requiring bleeding Hosts. The earliest Christians didn’t pass around cardiac tissue; they passed the cup. Their focus was on communion, not confirmation.

Fathers like Ignatius of Antioch and Justin Martyr affirmed the Eucharist as Christ’s body and blood, but their faith rested in Christ’s words, not in biological anomalies.

That’s important. It shows us that these miracles are not foundational, but occasional and devotional. They reflect culture and crisis more than doctrinal necessity.

What Eucharistic Miracles Might Really Be Saying

In some ways, Eucharistic miracles tell us more about the Church’s present than Christ’s presence:

- They reflect a crisis of catechesis, where basic Eucharistic theology is poorly understood.

- They expose a sign-seeking culture, more reliant on visual proof than spiritual trust.

- They speak to a hunger for intimacy with the sacred, a hunger the Eucharist already fulfils quietly at every Mass.

Perhaps they are not meant to convince, but to challenge: Do we need the spectacle, or are we willing to believe what’s invisible?

Questions on Eucharistic Miracles Answered

- What are Eucharistic miracles? Extraordinary events where consecrated Hosts appear to turn into flesh or blood.

- What does the Bible say? Scripture affirms the Real Presence but does not describe bleeding Hosts or flesh transformations.

- Are Eucharistic miracles scientifically proven? Most are based on biased or inconclusive evidence; peer-reviewed, independent studies are lacking.

- What is the theological issue? Elevating visible signs may unintentionally undermine belief in the Real Presence as taught in transubstantiation.

- How should believers respond? With reverence for the daily miracle of the Eucharist, without seeking spectacles.

Conclusion: The Host Is Enough

The Real Presence doesn’t need marketing. It doesn’t need to bleed. It doesn’t need scientific applause. It just is.

The Eucharist is the most radical claim in Christianity: that God is physically present in what looks like bread and wine. That’s already miracle enough.

If we need flesh to believe, maybe it’s not Christ who is absent, but our faith that’s fading.

“Blessed are those who have not seen and yet believe.” —John 20:29

That’s the faith the Eucharist invites us into, because He said so.

Leave a Reply